Earlier posts explained that the Swedish system of classifying organisations according to the products they produce (SNI) is useful as a tool to study the workings of the supply chains. The classification is connected to a lot of data collected about Swedish companies. This section covers the concept of allocation – that is about how much of common pool resources each type of industry takes up, and how much of the total need is filled by the respective companies. We will explore the theory in this part. The aim is to develop approaches that better inform policy making.

Let us start with what common pool assets are, otherwise called the commons.

We can all agree that we have only one Earth. And some things are used by everyone, often without paying for them. Examples include sunlight, the air, surface water etc. In earlier posts we explained that real capital is something that is used in the process of production, but not used up. This capital is a common pool resource, or a commons. Most interesting for this discussion is what corporations use in their operations that they do not pay directly for. In this post we will concentrate on natural capital – living capital, like forests, and mineral capital – like iron.

A commons…

… is real capital that is common-pool and employed within a community. Biological real capital is a common-pool used to harvest resources from or as a recipient.

Atoms are common pool assets. They are real capital as they are not used up. The living layer that emits oxygen is also real capital as this is not used up. What might be used up is the capability of the living layer to provide oxygen. The function of oxygen provision, a real capital function, could be compromised. There is a limited amount of oxygen atoms on the Earth, and a certain proportion of these atoms are in the air at any one time. So too is fossil carbon, contained in oil. The atoms might be real capital, but the energy in oil is not. When oil products are burnt, the carbon atoms remain as carbon, the energy in the fuel is used up.

Of course, the natural capital, oxygen, could be treated in such a way that it becomes no longer available to use in burning, for example if burning took up all the oxygen production.

We know from looking at Swedish statistics that most fossil oil is burnt in the transport sector, and coal is burnt in manufacture, service and housing.

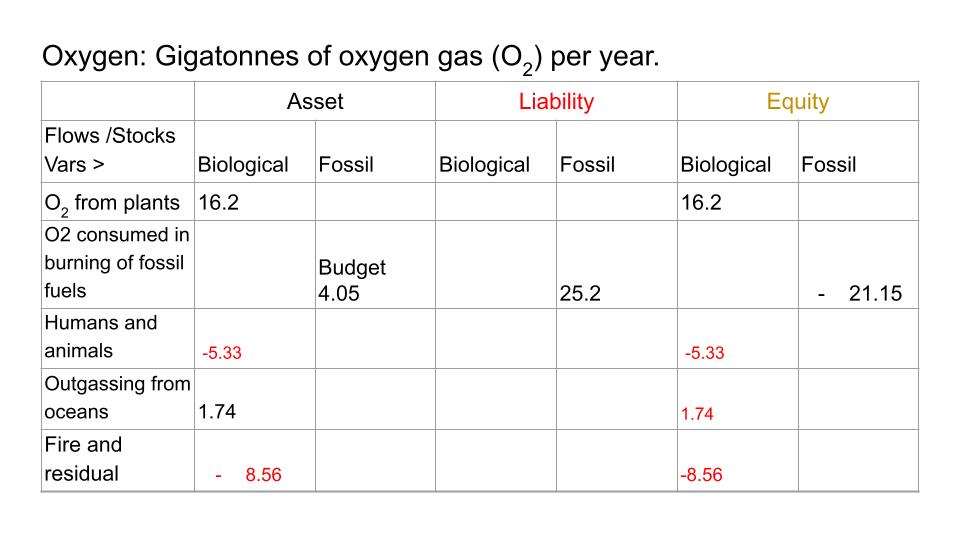

The diagram below shows current global oxygen use and the figures come from the paper by Huang, J. 2019 (See the references below).

The global plant and sea production of oxygen is at 17.94 Gt/year. However, the burning of fossil fuels exceeds this and creates a negative equity in terms of oxygen budget. There is however, a possibility to emit 4.05 Gt/year. This gives us a theoretical budget to work with, to allocate to companies.

The table below is a high-level thought experiment. If companies are going to use the public commons, then surely they should do it primarily for a public good. The table below shows how much of the oxygen budget is used up compared to the percentage of customers served. In the thought experiment below, one product is produced by two companies. Company 1 is less efficient, as by % of resources used should serve 40% of the population in need and it only serves 30. Company 2 is spot on. Company three serves another need with product type 3 and only uses less than a third of its allocated budget.

This is only a thought experiment, but it raises questions for policy, ones that would be pressing if this approach was applied to real figures.

- Which products should be allowed to use the budget – indeed which products from which countries?

- What can policy do about companies like (1) that use proportionally more of the resource to serve proportionally fewer customers?

- Overshoot. If use exceeds available resources, how should this be tackled? How will the effects of overshoot be born, and by whom? We will cover overshoot in coming posts.

At least from this cursory look, it is clear that market forces, that is to say those corporations who can pay most for the resource, should not alone be allowed to allocate common pool resources. The criteria will include efficiency – those who use the resources to serve most people, and purpose, that is to say uses can be prioritized. In our example cited above, fuel for transport might be restricted to the most efficient vehicles or for goods transport, or combinations.

One real life example might be how to craft policy to handle net zero by having not a carbon budget but an oxygen budget. This would include measures to increase the capability of land and sea flora to take up carbon. There could be a global dialogue on which industries could purchase fossil products, and within those, criteria against which to prioritize organizations and the amount apportioned to them.

At least it looks as if the approach – of identifying products or product categories and matching them to resource use and the effect on real capital, could be developed to provide a clearer decision basis than one merely based on economic data.

References

Huang, J., Huang, J., Liu, X., Li, C., Ding, L., & Yu, H. (2018). The global oxygen budget and its future projection. Science Bulletin, 63(18), 1180-1186

One thought on “The ABC of supply chains. Allocation of common pool assets and services based on them.”