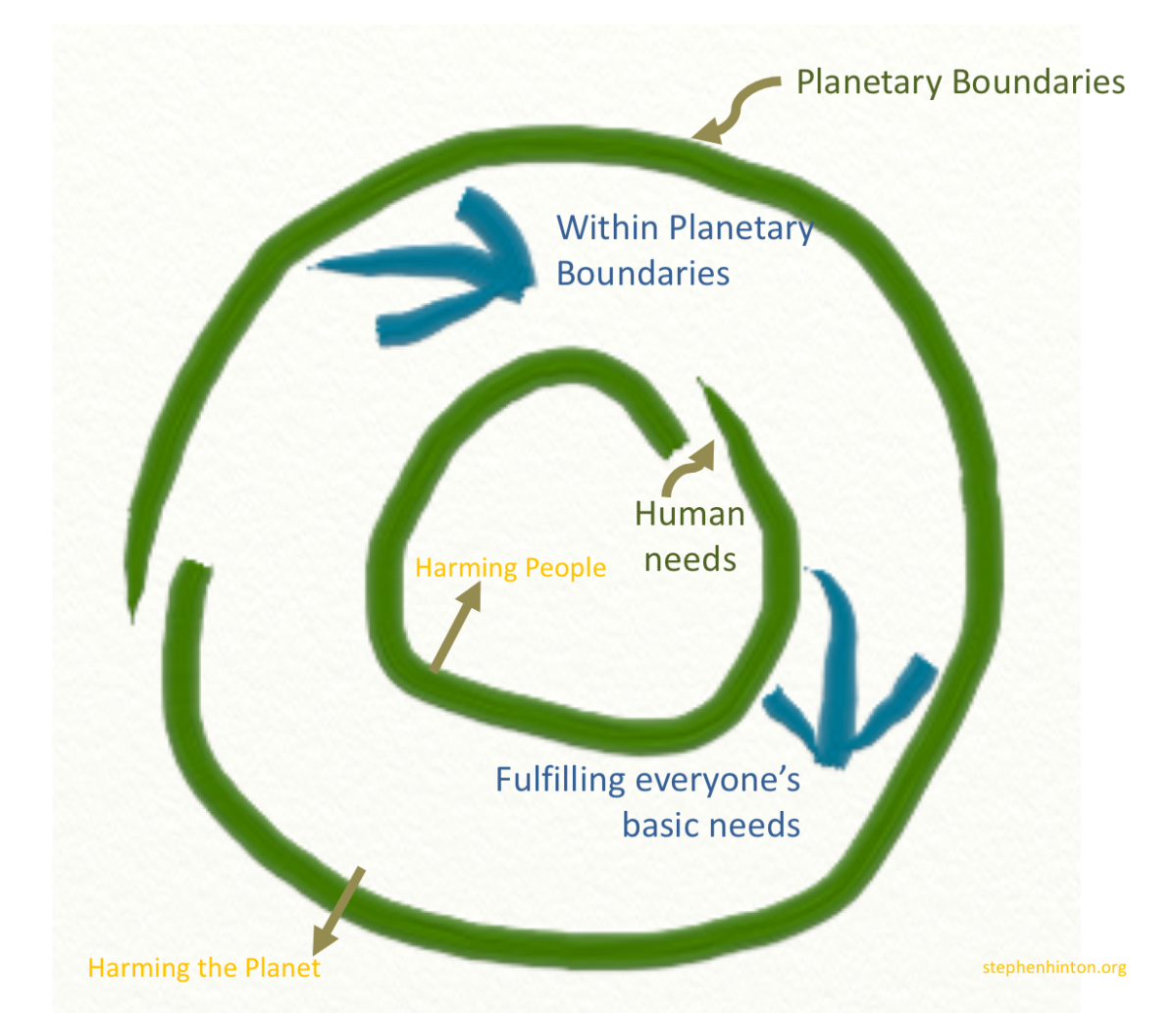

Kate Raworth has a wonderfully clear and simple concept – that we should arrange the way we run society on the principle that we do not exceed planetary boundaries – in our relation to nature – on one hand, and that we set things up to avoid people suffering and that everyone’s basic needs get fulfilled – the human dimension – on the other. She draws it like a doughnut.

In her excellent book, Doughnut Economics, Kate shows how this task is essentially one for the economy and a question for economics. Doughnut economics gives us a very clear set of requirements for how an economy should work. That immediately brings one to think of money, investments, taxes, banks businesses etc. And that is where the model needs a little help .

It is a great visual model for explaining how our human activities – including the ideas some have around the possibility of infinite economic growth – should not perform environmentally or socially. However, It does not get down to the nitty gritty of what transactions are allowed and which are not and who should pay whom for what at which price in order to reach that balance.

The doughnut misses out the essentials of economy itself – the transactions between people, organisation and nature. The theory requires that there are constraints and stimuli make sure the economy functions to requirements. (Doughnuttedly?). Without identifying these it is hard to see where the theory has practical applications.

This is serious because we have only a few years to defossilize the economy and there is a great danger that poor people will suffer. Indeed poor people in the world are already suffering so we need something that will help transform society fast.

The Bathtub model of the economy

So we need another model – one as equally simple and clear – to help us understand this “economy”. And then a way to put the models together.

Enter the bathtub. The bathtub is a model of how the economy works developed by TSSEF to help people engage in economics, a subject otherwise seen as some kind of dark unfathomable art. The bathtub is a model that helps people visualize how the economy works and how it impacts the natural world. It also helps people see how economic incentives can influence behaviour of the system, including buying behaviour of consumers and organisations and importantly, the environmental and social performance of the system.

Picture a bathtub with water representing the combined money and assets owned by citizens in a bathtub – and the top layer is liquid. That is the money we use to pay our bills every month. This money goes to corporations as bills paid, to government as taxes, and municipalities as taxes and charges for services.

Every month, the money returns to citizens in the form of wages and benefits from the same organisations.

The model shows some things clearly:

- It is possible to control the flow of money by adding constraints like taxes and fees (the triangular symbols in the diagram).

- It is the speed of circulation of money as well as distribution that affect the performance of the economy. If money stays in one place too long, or accumulates (for example with a government surplus) the system breaks down – citizens cannot pay their bills and rich people’s factories turn out goods no-one has money to buy.

- Everything in the economy is people and the big bathtub. People own corporations and people are represented by government. It is all people controlled.

- As long as people have money to buy stuff the system turns over.

Putting nature into the model

In doughnut terms, people need to have enough to buy what they need. But that is the easy part of the doughnut. I guess people will wonder about jobs and the environment. What is the point of the job you have if it is killing the planet – where are the green jobs? To answer this we need to ask where nature comes into the bathtub model. – Well, that is a tricky thing because you can see from the diagram that money is just circling around and nature does not seem to be involved. Nature is involved in fact in what we call the first invoice. The first invoice is the one that nature does not send but where the firm extracts or harvests something from nature (energy, vegetables, wood, metals etc) and sells it on.

And then there is the last invoice – where the material leaves the economy and never circulates in it again. Some things end up as landfill – where citizens pay a service to cart away their rubbish.

The economic system currently relies mainly on rules and regulations to limit extraction from nature and deposition of waste into nature. Extraction of potential pollutants is only limited by it economic viability – rather than its environmental viability.

What the bathtub model offers, however, is that the first and last invoice represent entry and exit to the economy and can act as regulation points.

The most effective economic regulation is to add an additional tariff to extraction/harvesting, one that can be changed according to the pollution situation. Additionally, to keep money circulating in the system, the levy collected should be distributed back to citizens.

Additional tariffs on unwanted things are rather like the way city congestion charges work: you get charged most if you drive into the city at peak times.

The Carbon Dividend is an example of economic control

A good example is the Carbon Dividend of the type introduced recently by Canada that fits into this model. It is an extra levy on fossil carbon introduced into the economy that will be raised until the economy de-fossilizes at the rate determined to result in safe emission levels. The levy makes fossil-carbon containing products more expensive as the levy is passed onto final consumers. At the same time, collected fees are redistributed to taxpayers as a dividend meaning those whose purchase a lot of fossil carbon will end up with less in their pockets relatively speaking. Those who purchase less will be net gainers. The dividend mechanism applied at import then, and raised until the market changes, can be used to influence the buying behaviour of the entire society.

Indeed, if you look at the bathtub model, you will see several more transaction types that offer opportunities to regulate the relative price of things. And that is the point: to find ways to make (relatively,) counter – doughnut behaviour expensive, and pro doughnut behaviour cheaper.

Control mechanisms – with fast feedbacks – are the future

The bathtub model mirrors the well-known concept of control engineering. In control engineering the main components are: a physical system (like a car’s braking system) a digital control system connected to the physical system and controls (in this case the brake pedal and the braking system) and an actuator that controls the physical system (a brake) and a sensor that provides information to the digital control (in this example a sensor that tells if a wheel locks). The digital system is able to use feedback from the sensor to calculate what to do and to apply physical controls. In this case, if the wheel locks when braked, to release the brakes momentarily.

So how would control engineering be applied to the economy? Well, the physical system is the bathtub model, the sensors are statistics, depending on what is being controlled, of economic performance such as unemployment, fossil fuel burnt, emissions of nutrients to watersheds, etc. The actuators are the “brakes” in this case supplemental levies (could be negative) on existing taxes and fees.

If feedback from say, statistics of fossil carbon in the economy show that targets are not being met, the supplemental levy on fossil import is raised slightly. At the same time, as the fees are collected, more goes into people’s accounts. If targets are still not met later, the levy is raised again until targets are met.

What is sweet about this is that people see that the ones who buy a lot of products with pollution in them will pay more. And those who buy less will get more money in their pockets. Fair and transparent! It also gives the market clear signs about what to invest in… that non-polluting products will become relatively cheaper and therefore more attractive.

This approach gets away from people feeling they ought to buy more expensive products that perform better environmentally on the one hand, when they have limited budget on the other.

The whole system requires digital control, because the feedback needs to be accurate and timely- and the mechanism for charging the supplemental levies needs to be updated fast after decisions to raise or lower are made.

If you want full employment you can have it – your way

This has little to do with your political persuasion – it is pure economics. Politics is more about what you encourage to create a solution as we shall see in the example below.

Lets us take employment as an example. Let’s say that inclusion is important in a particular society and there is consensus that everyone should have a job. What to do if there are large numbers unemployed?

Total employment (E) is the sum of the numbers working in firms (F), municipalities (M) and government (G)t.

E= F+M+G

From the bathtub model you can see that increasing employment requires introducing economic stimulus in one or more of the dimensions.

You could, for example:

- reduce employer’s taxes and other taxes to stimulate firms to employ more by adding a negative supplemental tax.

- add a fee to increase VAT and use the income to employ more at Government level.

Take as an example employer taxes. These are added to the price of the goods consumers pay for. So if you increase employer taxes you make the price of the product higher and maybe consumers are less likely to buy it if there are products around that use less labour for example.

Or you could do it the other way around – put a negative levy on company taxes so products where the higher the percentage of wages is in the end price the lower the company tax.

So in the bathtub model you start to see opportunities to adjust supplementary fees on taxes and possibly change the behaviour of the system.

With Doughnut and Bathtub you don’t need GDP

Another beauty of the bathtub model is that it gets down to specifics and deals with them directly – side-stepping the need to look at GDP as a proxy. Today, specific statistics are easy enough to collate in the digital economy.

You might be wondering about the roles of banks, financialization of the economy and currency and a load of other things. Well, banks are enterprises that act as intermediaries according to many Nobel Economics prize winners. We have other ideas but they can still fit into the bathtub model, but in this version it is enough to explain the day to day runnings of the economy. We can get back to you with a treatise on the role of the banks in all this, balance of trade etc.

For more information on the bathtub model do see the Swedish Sustainable Economy Foundation’s Website http://tssef.se .

2 thoughts on “Why the doughnut needs the bathtub – economic models for real change”