The last article explained that, if you are looking to develop policy to drive the circular economy, then it is useful to divide supply chains up in their industrial classification. You need to look at one in particular, the keystone holding it all up – C, manufacturing. And in manufacturing, you need to focus on built capital – the capability and performance of the actual infrastructure used in manufacturing.

Manufacturing can drive the circular economy

The reason for this is that the manufacturing infrastructure in place has the capability of determining to a large extent the behaviour and performance of the whole. If we see the supply chain as circular – from material stock to product to stock – then the manufacturing infrastructure sits in a critical position. It can both determine what inputs it takes in, and the products and waste it sends out.

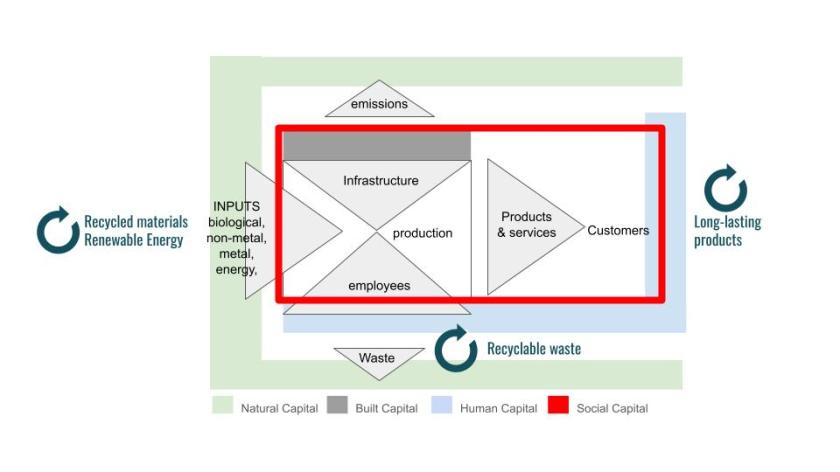

You need to see the way the firm, the unit of the supply chain, works. And we see it through the eyes of the four types of capital.

The firm is a social capital. From right to left, working backwards, customers (human capital) pay for products, and the money taken in pays for employees (human capital) and for inputs (natural capital). However, without the machines and tools, little can be manufactured. This is the built capital or infrastructure. Capital, is that which, in the production process is used, but not used up.

The ideal circular economy firm is one with infrastructure that:

- makes long-lasting products

- emits carbon dioxide from natural sources only in amounts that nature copes with

- produces waste that can be recycled

- uses inputs from renewable resources.

Indeed, it is theoretically possible to look at each firm, or group of firms or indeed the whole infrastructure in this way, based on this normative (should be) formulation.

If you want society to function in a circular way, then manufacturing infrastructure should be able to perform to the levels above, and actually perform to levels above.

PHILOSOPHIA OECONOMIA CIRCULARIS PRINCIPIA NATURALIA

These two – capability and actual performance – are different. For example, an internal combustion engine can theoretically run on both biofuels and fossil fuels. It could be that manufacturing is buying fossil fuel because it is cheaper. So it has the capability but it is not realising it. For policy, then, it has to address the price differential.

Each manufacturing industry should be analysed

To the analysis we should also add BAT-Best Available Technology. This will indicate if the firm(s) have invested in the latest available or are using old technology.

The analysis then arrives at something that could be represented by a high -level diagram like the one below, which visualises capability performance and the normative levels needed. The diagram is figurative only.

For anyone working with policy, then, this kind of analysis should inform what needs to happen. Were the above an actual industry it would be clear that investment in development of technology (or practices) to create recyclable waste is a priority, as the existing infrastructure is capable of using recycled waste.

The other policy area is product life-time, where the capability exists but is not being used.

In summary, the approach of analysing the performance, capability and potential of installed infrastructure against environmental norms should provide sound decision basis for policy. The approach is not comprehensive however, more dimensions need to be explored, like how much certain industries are allowed to use common-pool resources, and how effective they are in serving the whole population, rather than a select few.These and other aspects we will address in future articles.